Does the rebranding of goods before they are imported into the EEA violate the rights of a Union trademark? The Advocate General of the ECJ yesterday ruled in the conflict over the de-branding and rebranding of Mitsubishi marks on forklifts. Thus, important questions on trademark law in the EU were assessed: Limits on the rights of the trademark owner and control of the first placing on the EU market.

Background of the case

The plaintiffs are Mitsubishi Caterpillar Forklift Europe BV (MCFE) based in the Netherlands and Mitsubishi Shoji Kaisha Ltd (Mitsubishi) based in Japan. Mitsubishi manages the Mitsubishi Group’s trademark portfolio worldwide – it is the owner of several word and figurative trademarks in product class 12. MCFE has the exclusive right to manufacture and market Mitsubishi forklifts in the European Economic Area.

The plaintiffs are Mitsubishi Caterpillar Forklift Europe BV (MCFE) based in the Netherlands and Mitsubishi Shoji Kaisha Ltd (Mitsubishi) based in Japan. Mitsubishi manages the Mitsubishi Group’s trademark portfolio worldwide – it is the owner of several word and figurative trademarks in product class 12. MCFE has the exclusive right to manufacture and market Mitsubishi forklifts in the European Economic Area.

The opposing parties are G.S. International BVBA (GSI) and Duma Forklifts NV (Duma), a company based in Belgium. It is mainly active in the worldwide purchase and sale of new and used forklift trucks, mainly of the Mitsubishi, Caterpillar, Nissan and Toyota brands. GSI is a company associated with the Duma, with the same management and the same registered office, also located in Belgium.

According to the order for reference, between Jan 2004 and Nov 2009 the Duma and GSI operated illegal parallel trade in forklifts on which the Mitsubishi brands were affixed without the trademark owners’ consent. However, this behaviour is not the subject of the questions referred.

Since November 2009, Duma and GSI have purchased forklifts from a company of the Mitsubishi Group and transferred them to the customs warehousing procedure. While the forklifts were in the customs warehouse, the two companies took the following actions:

- Complete removal of Mitsubishi brands from forklifts,

- making the necessary changes to adapt the trucks to the standards in force in the Union,

- Affix your own marks on the trucks and replace the identification plates and serial numbers with your own,

- and import and sale in the EEA and third countries

Mitsubhishi and MCFE brought an action before the Brussels Commercial Court before 2008, seeking an injunction against parallel trade and the removal and reinstallation of the marks. The first instance dismissed the action in 2010 and the plaintiffs appealed against it.

The questions referred

The Brussels Court of Appeal (Hof van beroep Brussel) referred the following questions to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) for a preliminary ruling:

- Comprises Article 5 of Directive 2008/95/EC and Article 9 of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 June 2009 on the protection of the environment. (2) On the Community trade mark (codified version) of 11 February 2009, the right of the trade mark proprietor to oppose the removal (debranding) by a third party without his consent of all signs which are affixed to the goods and which are identical to the marks in the case of goods which have not yet been marketed in the European Economic Area, such as goods entered for the customs warehousing procedure, and the removal by the third party with a view to the import or placing of the goods in or on the market. in the European Economic Area?Does the answer to this question depend on whether the goods are imported or placed on the market into or within the European Economic Area under a third party’s own identification mark (rebranding)?

- Does it affect the answer to question 1 if the goods thus imported or placed on the market are still identified by the relevant average consumer as originating from the trade mark proprietor on the basis of their external appearance or model?

This is a tricky and important case involving not only Community trade mark law but also customs legislation and unfair competition rules.

Arguments of the Duma:

The proprietor of a trade mark may not object to the importation into the Union of original trade mark goods bearing the trade mark which had previously been placed on the market in the customs warehousing procedure but not in the EEA. Since no sign identical or similar to the Mitsubishi brands is used, the perception of the average consumer is completely irrelevant.

Arguments of Mitsubishi:

The special purpose of the trade mark right is to enable the trade mark proprietor to check the first placing on the market. The proprietor of the trade mark has the right to’oppose the fact that a third party, without his consent, removes the signs affixed to the goods in so far as they are goods which have not yet been marketed in the EEA, as in the case of goods entered for the customs warehousing procedure’. A trademark also has several functions that have been infringed: the guarantee of the origin and quality of the goods, the investment and advertising functions.

Political level of the questions referred

The German Government is in favour of a negative answer to the questions referred: the complete removal of the mark does not infringe any of the functions of the mark. It follows from the wording of Article 5 of Directive 2008/95 and Article 9 of Regulation No 207/2009 that the exercise of rights arising from the trade mark presupposes’use’ of the mark, a term which must be interpreted equally in both provisions, argues the German Government.

However, the European Commission is in favour of an affirmation of the issues raised. The Duma and GSI had used the customs warehousing procedure to transport the forklifts into the EEA with the aim of handling their importation in the prescribed form; in this case it was irrelevant that the removal of the marks from the goods could be illegal from the point of view of unfair competition, according to the Commission.

In his Opinion, yesterday the Advocate General focused on the aspect of use or non-use of the trademark, i.e. the provisions of Directive 2008/95 and Regulation No 207/2009 governing the rights of a trade mark proprietor.

Opinion of the Advocate General

The Advocate General considers that the complete removal of the mark does not constitute use of that mark (Article 5 of Directive 2008/95/EC and Article 9 of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009). Because the trademark must be used “in the course of trade”. The goods had not previously been placed on the market in the European Economic Area because they were in a customs warehouse. Consequently, no consent of the trademark owner was required for trademark removal.

It is also crucial, however, that the signs were removed with the aim of placing these goods on the market with a new trademark in the European Economic Area. Moreover, the goods were “changed in their structure while in the customs warehouse” in order to adapt them to the technical standards in force in the Union. And it is also essential that the new brand differs from the original one.

Nor does the Advocate General consider that the defendant’s conduct is fraudulent or abusive. Because as long as the goods are in the customs warehousing procedure, they are not yet in the EEA from a legal point of view. This would correspond to direct imports from third countries. The proprietor of the trade marks may not oppose release for free circulation in the EEA of goods intended for consumption if his trade marks are not perceivable as such to the consumer.

National law varies in the Member States of the Union

This does not affect the national jurisdictions of the Member States in the Union. While both British and German case-law do not regard the complete removal of a trademark as a trademark infringement, this is explicitly a trademark infringement under French law. The French legislature has formulated a separate ban on trademark removal (Art. L 713-2 of the Code de la propriété intellectuelle). This is relevant because there is no EU legislation on unfair commercial practices among entrepreneurs. In order to combat such practices, the national law of the Member State must be applied.

Are you interested in brand or trade mark protection?

Please take your chance and contact us. Our lawyers are experienced in trademark and patent law, national and international law.

Souces:

Curia Europe: C‑129/17 (in French)

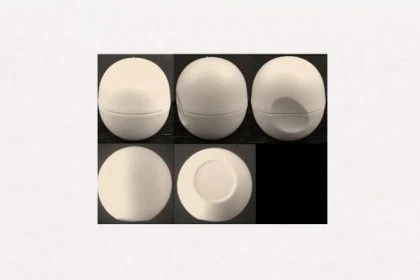

Picture: